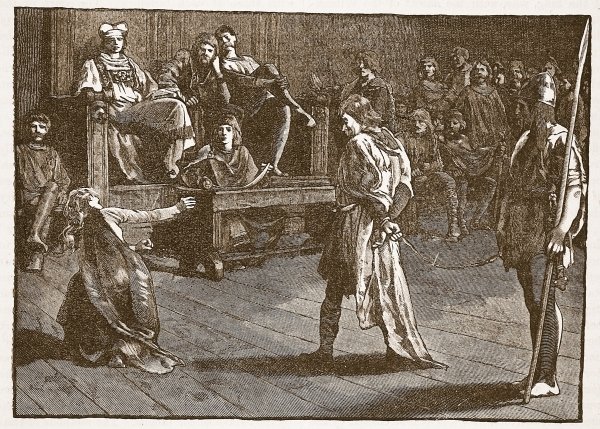

As god of the Þing

Tīw was connected to the ‘thing’ or Germanic law assembly. Some of the earliest mentions of a Tīw-like deity in Britain come from inscriptions found at the fort of Vercovicium at Hadrian’s Wall. The inscriptions refer to a ‘Mars Thincsus‘ or a ‘Mars of the Thing‘ and is believed to have been written by Frisian mercenaries during the 3rd Century CE in reference to Tiw.

Tacitus also describes a deity associated with both law and battle in Germania, who was consulted in matters relating to capital punishment.

” But to reprimand, to imprison, even to flog, is permitted to the priests alone, and that not as a punishment, or at the general’s bidding, but, as it were, by the mandate of the god whom they believe to inspire the warrior.”

(Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb trans.)

There is also an interesting clue present in the modern Dutch days of the week. The Dutch name for Tuesday is ‘Dinsdag‘ which translates to ‘Thing-day’, once again linking Tīw, who our Tuesday is named after, with the Germanic lawful assembly.

As god of war and Glory

In Germania, Tacitus refers to a ‘Germanic Mars’ when listing the chief deities of the Germanic tribes. Many scholars have taken this as a reference to Tīw, citing the similarities between the Roman war god and later depictions of Tīw within Norse mythology. Unlike the Greek Ares, who was seen as a chaotic and destructive force, Roman Mars was a god who used war as a way to create cohesion and peace. This description would be loosely consistent with Tyr’s combined role as both god of war and of law.

In Norse sources, Tīw’s (ON: Týr) position as heroic war deity is pushed to the fore, with his defining moment occurring during the binding of the wolf Fenrir.

“Yet remains that one of the Æsir who is called Týr: he is most daring, and best in stoutness of heart, and he has much authority over victory in battle; it is good for men of valor to invoke him. It is a proverb, that he is Týr-valiant, who surpasses other men and does not waver. He is wise, so that it is also said, that he that is wisest is Týr-prudent. This is one token of his daring: when the Æsir enticed Fenris-Wolf to take upon him the fetter Gleipnir, the wolf did not believe them, that they would loose him, until they laid Týr’s hand into his mouth as a pledge. But when the Æsir would not loose him, then he bit off the hand at the place now called ‘the wolf’s joint;’ and Týr is one-handed, and is not called a reconciler of men.”

(Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur trans.)

The rune associated with Tīw also seems to have been used by warriors to find glory both in battle and in the afterlife. The ‘Tir’ rune appears on more funerary urns in Anglo-Saxon burials than any other symbol. In Sigrdrifumol the Valkyrie Sigdrifa suggests Sigurðr carve the symbol twice onto his sword hilt to gain victory in battle.

‘Winning-runes learn, | if thou longest to win,

And the runes on thy sword-hilt write;

Some on the furrow, | and some on the flat,

And twice shalt thou call on Tyr.’

Although the Anglo-Saxon ‘Tir’ rune poem seems to refer to the North Star, or another such celestial body, it has the words ‘fame, honour’ written alongside the rune establishing a possible connection with the god of the same name. Perhaps this was merely a case of Christian censorship or perhaps there was some connection between the god and the celestial body mentioned in the poem.

” Tir is a (guiding) star; well does it keep faith

with princes; it is ever on its course

over the mists of night and never fails.”

(Bruce Dickins trans.)

As Sky-Father

During the Victorian period and well into the mid 20th Century it was fashionable to try and depict Tīw as the supreme god of the Germanic pantheon. This assertion was based almost entirely on the idea that Germanic ‘Tīw’ was descended from the reconstructed Indo-European Sky-God ‘Dyēus Phatēr’. While the linguistic similarity between Tīw and Dyēus is fairly concrete (Proto-Germanic *Tiwaz being etymologically linked), the theory that the ancient Germans worshipped him as a sky-god has little backing evidence.

Brian Branston makes arguments in favour of Tīw being worshipped as a sky-father figure right up until the Migration Period, although his supporting evidence is weak at best. He draws heavily from Snorri’s words, claiming that since the Eddas claim the Allfather was present from the beginning of time and Wōden was born AFTER this fact, that he couldn’t possibly be the Allfather figure described in the Eddas.

“But Odinn did not live from the beginning of time; he was not just there, but was born from the union of the god Bor and the giantess Bestla; nor did Odinn ‘rule his kingdom with absolute power’ – he was at the mercy of Fate: both Snorri and the ancient verses are agreed on these points. There can be no doubt that the Allfather and Odinn (no matter how they got mixed up later on) were originally two different personages.”

Assuming the Eddas to be some infallible glimpse into the elder religion is dangerous. Anyone who has actually read through the Eddas knows they can be confusing and are often contradictory. Hardly the appropriate place to look to prove a point about Tīw being the supposed lost Sky-Father of the Anglo-Saxons, anyway.

It is entirely probable that Tīw did descend, at least his name did, from the Proto-Indo-European Sky-Father, though it really isn’t a question of IF, but a question of WHEN the changes to his nature occurred. The shift from Sky-Father to martial/law deity may have occurred long before the Germans became a distinct cultural entity.

I find Tiw to be inspirational as a god, given what he sacrificed for the greater good, and a worthy god to make my oaths to. For me, his strength is in the lesson he teaches us all – he gave his hand knowingly, deliberately for the betterment of all existence. That is a very noble and brave act. In our own Innangeard’s, there is much to be learned from his example. For me, I take inspiration from him and think of his sacrifice whenever I have a dilemma to consider between what is best for me compared with what is best for my Innangeard, and to some extent my Ūtangeard. Whereas Woden inspires me to make personal sacrifices for personal gain, particularly with regards to personal development and knowledge, I find the relationship with Tiw is far more around the relationship with my Innangeard, and also to the Ūtangeard particularly with regards making the right decisions that are fair and honourable with regards to them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure if my last attempt to comment was picked up, but in any event I find Tiw to be a source of inspiration given the sacrifice he made for the betterment of all existence. He gave his hand knowingly and without hesitation and thus made a great and noble sacrifice that we have all benefitted from. From my perspective he shows me exactly why sometimes one has to sacrifice self-interest for the betterment of one’s Innangeard or Ūtangeard on some occasions. Whereas Woden teaches me that the pursuit of knowledge and thus personal development is a worthy thing requiring sacrifice and pain, Tiw teaches me that sometimes that sacrifice and pain must be considered when exemplifying this interests of one’s Innangeard and, to some extent when considering one’s Ūtangeard. I find him a worthy god to make my oaths to, and an inspiration that we can all learn from.

LikeLike

It’s important when dealing with the Ūtangeard to be wary, yet diplomatic. It wouldn’t be good for your tribe if you were consistently a horrible miser to everyone outside your Innangeard, now would it? What’s good for the tribe is good. That being said, be cautious. The Ūtangeard is the wilderness, chaos, uncultivated. Grith is temporary and does not bind us as frith does. Frith cannot exist between strangers.

LikeLike

Sound advice. Ever vigilant. Ever wary.

LikeLike

I suppose I should add that given my work places me squarely in the Utangeard with particular emphasis on upholding the laws of the land, that is why I can see and feel a particular pull towards sacrificing aspects of my own self so as to achieve results for the benefit of society as a whole. I see these sacrifices as necessary, on occasion, to get the job done. My sacrifice is of course nothing like Tiw’s, albeit I run a physical personal risk on a daily basis simply due to the nature of the work, however I regularly give up my time, money and plans for the benefit of the Utangeard, and for me the balance I need to maintain must surely be weighted in favour of my Innangeard, and that is why I find Tiw such an inspiration to me and a constant reminder to try and keep that balance. Sacrifice, yes, but in moderation and not to the detriment of one’s Innangeard, which is everything. Some of my ancestors were involved in a similar line of work and I look to them for inspiration also. Tiw represents that honour, dignity and justice that I seek to emulate and that is just another reason why I find him such a magnificent, if sometimes overlooked god.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I do wonder, though. Are you making these sacrifices for the Ūtangeard? Or are you making them for your Innangeard indirectly?

LikeLike

Yes I pondered this after I wrote it. My Innangeard does directly and indirectly benefit from the sacrifices I make for doing what I need to do for the Utangeard, therefore it is not as clear cut as saying I am solely making sacrifices for one or the other. The point is, rather, that I must recognise if the relative “cost” of the sacrifice is not weighted towards my Innangeard, directly or indirectly, then it becomes an issue in need of redress. I have learned the hard way that the Innangeard is everything and must take priority or else risk losing everything that has real meaning.

LikeLiked by 1 person